Are Story Types a Help or a Hindrance?

What Kurt Vonnegut, Joseph Campbell, and Garry Shandling have in common

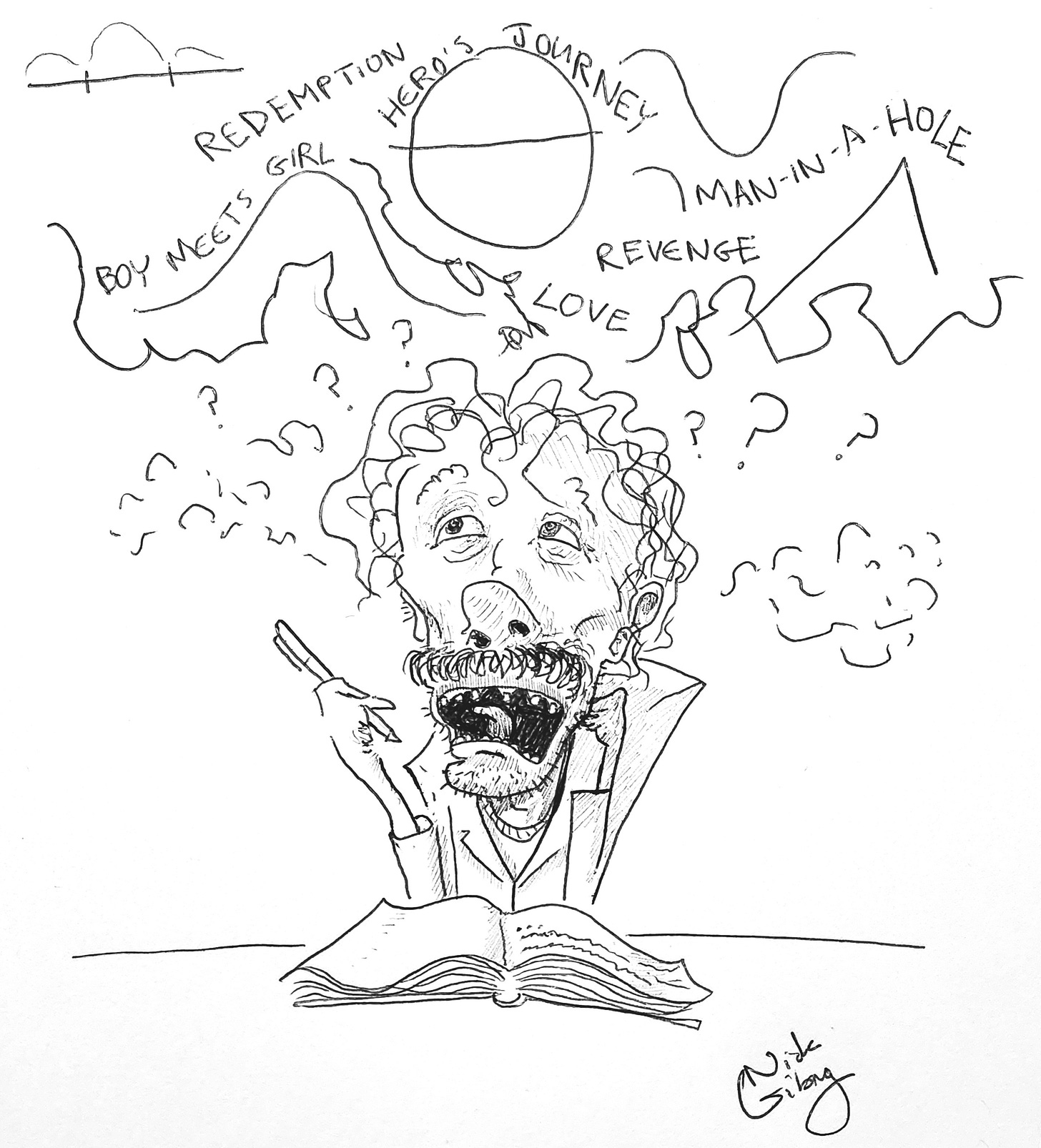

There are a lot of theories—probably too many—about what a good story looks like, how to structure it, and how many different stories there actually are to tell. Writers like me seek these out because we want a map for a writing journey that can feel at times like being lost in the woods without a flashlight, even if we know deep down that the only map that really works is the one that keeps the reader turning the pages. Two of my favorite ideas about structure are Kurt Vonnegut's Shape of Stories lecture and Joseph Campbell's Hero's Journey.

In his lecture, Vonnegut eloquently illustrated the point that, while there are many familiar shapes that we can use to make a successful story, there are comparatively shapeless stories, like Hamlet, that are just as successful.

Structural archetypes are useful as long as we don't mistake them for universal truths. Because, as Vonnegut points out, we don’t have enough information about life to unequivocally know the good from the bad, the true from the untrue.

Joseph Campbell, known for his theory of the monomyth, otherwise referred to as the Hero’s Journey, is often criticized for trying to make sense out of the human experience by reducing diverse myths from around the world into one essential story. There are plenty of stories that do not tell a step-by-step Hero’s Journey. But Campbell would agree with that. It merely attempts to recognize the common aspects of the search for who we really are inside, by finding commonalities in folktales, myths, and other stories from around the world.

The comedian Gary Shandling, in response to a question about how his journey into Buddhism affected his comedy, said:

All my journey is is to be as authentically who I am, not trying to be somebody else under all circumstances. The whole world is confused because they’re trying to be somebody else. To be your true self, it takes enormous work. Then we can start to look at the problems of the world. But instead, ego drives it; ego drives the world; ego drives the problems. So, you have to work in an egoless way. This egolessness, which is the key to being authentic, is a battle. And it’s a battle that has to be won before we’re worried about the economy.

Garry Shandling is essentially describing the spiritual journey of Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces. And isn’t this search, the search for inner meaning, at the heart of all the shapes in Kurt Vonnegut’s graph as well? Even if the search ends in tragedy?

The Hero’s Journey is not ethically prescriptive either; it does not seek to determine a right or wrong way to be human, because what makes a hero is a matter of perspective. Just as a villain serves as a metaphor for some internal obstacle within a hero, the inverse is also true. From the antagonist’s point of view, the hero is the villain, and serves as a metaphor for the anti-hero’s struggle. Each character has their own spiritual mission, whether they are conscious of it or not.

The roles that are not often talked about in the Hero’s Journey, however, are the roles of theme and metaphor. The obstacles, interactions, and transformations within Campbell’s framework can all be used as metaphors for the central themes of a story. But if they don’t, then a story that uses the Hero’s Journey as a map only does so in appearance. In other words, you could write a story that fulfills the Hero’s Journey criteria to a T, and still miss the point of the quest entirely. For example, many Coming of Age stories follow the Hero’s Journey framework because the “departure, rebirth, and return” shape of the journey serves as a solid metaphor for the transformation from childhood to adulthood. The themes line up with the goals of the journey. But let’s look at the inverse. The movie Dude, Where’s My Car?, for example, is a step-by-step Hero’s Journey. But that movie is about nothing. Without a concrete theme tethered to the Journey through metaphor, the structure is meaningless; it’s all style and no substance.

So, do the stories shapes Kurt Vonnegut laid out contain some aspect(s) of the Hero’s Journey?

His “Man-in-a-hole” could be, for sure. So could Cinderella, at least in parts. You might think that you'd have to really stretch your imagination to fit Kafka's The Metamorphosis into some part of the journey, but the clue is in the title. Stories of transformation are integral to Campbell's theory, even if they don’t have a typical resolution. Hamlet, in the end, tests the value of adhering too strictly to theory. But there is no doubt that Shakespeare understood the tricks of his trade, what worked and what didn't, what audiences expected and how to play with those expectations through subversion, fulfillment, or intentional ignorance. In other words, you need to know the rules so you can break them.

Some theorists believe that there is only one type of story. Others claim four. Some claim seven, others twenty, and others thirty six. If these differing numbers don't give you a clue that it's all bullshit, then I don't know what will. But, as the great Chuck Wendig once said, “bullshit still works as fertilizer.”

What I’m Reading Now:

Oedipus the King by Sophocles

Deathbird Stories by Harlan Ellison

Gallant by V.E. Schwab

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Nick Gibney’s Story Board to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.