When you hear the word Steampunk, what comes to mind?

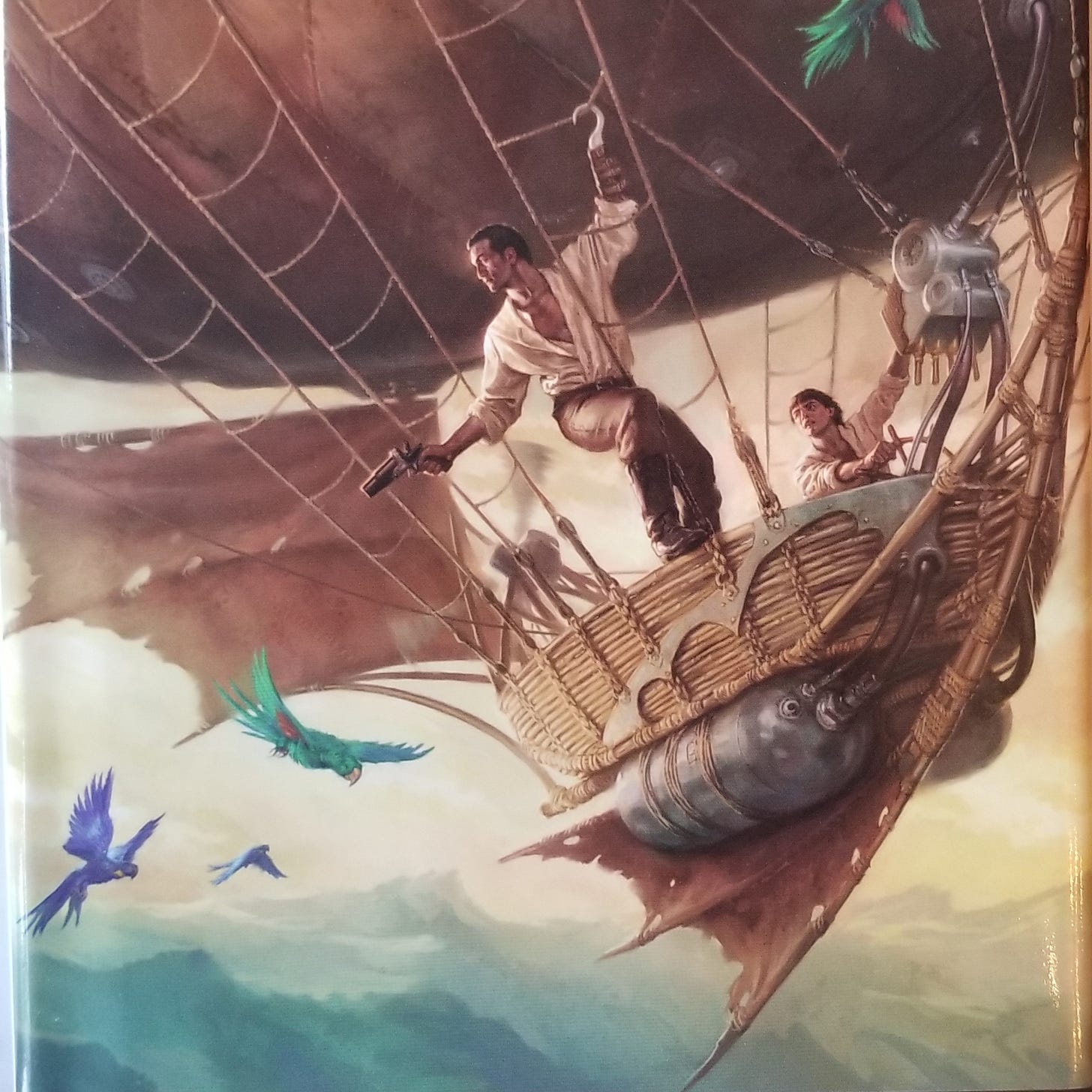

Top hats and monocles, dirigibles, anachronistic brass clocks, the Victorian era, and—probably—steam power.

Or, in the hilarious words of Key & Peele, “Jules Vern and shit.”

But what is steampunk, really? It’s a sub-genre of science fiction, yes. But it often includes elements of fantasy as well. So let’s just say it’s a sub-genre of what Margaret Atwood aptly calls Wonder Tales, stories that are not naturalist.

But what the heck is a genre? And do you see where I’m going with this?

A genre is just a set of expectations.

You can either deliver on those expectations, or subvert them. But the more specific the sub-genre is, the more specific the expectations are. For this reason, I think sub-genre labels are actually more helpful than the broader genre labels when describing, or recommending, science fiction and fantasy works. Bookshelves at the bookstore should get way more specific. For example, Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, which—retroactively—fits within the sub-genre of High Fantasy, carries a very different set of expectations than Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere, which can best be described as Urban Portal Fantasy. So if someone was looking for a recommendation and told me they liked fantasy books, expecting me to give them something with dragons and swords and elfin princesses, they might be sorely disappointed when I give them Neverwhere.

It’s for this very same reason, this specificity of expectations, that Margaret Atwood preferred the term speculative fiction in relation to her dystopian MaddAdam trilogy and The Handmaid’s Tale. It’s also possible—as Ursula K. Le Guin pointed out in her review of Atwood’s The Year of the Flood— that she preferred Spec-Fic because she did not want her novels dumped in the literary ghetto of Science Fiction.

Maybe. But I actually think that it had more to do with her artistic intent. Which brings me back to Steampunk.

What is the point of Steampunk?

It asks that classic sci-fi question: “What if?” In this case, “what if steam technology advanced so much in the 19th century that things got way more futuristic than they were?” This sounds cool in theory. Proto-steampunk authors like H.G. Wells and Jules Verne did it with The Time Machine and Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. But unfortunately, these influences bog down most contemporary steampunk with a romanticized view of the Victorian era that includes little to no examination of its imperialism or colonialism. This plays out in the shape of unfortunate “What if” questions, like what if Great Britain was even weirder and cooler because of steam powered gizmos? Or, what if I don’t make it back in time for afternoon tea because my dirigible broke down? Or you’ll find people at Burning Man wearing corsets, with clock gears glued to their top hats, using dainty umbrellas soldered to their brass plated bicycles to keep from getting heatstroke. Basically, steampunk has, at best, become more about its anachronistic aesthetics, and at worst, has become an unwitting tool of the status quo. Which is ironic, considering its name is founded in a counterculture movement.

Basically, a lot of so-called steampunk authors forget about that second syllable:

PUNK.

But don’t lose hope. There are some true steampunks still out there. When done right, these stories are some of the best Wonder Tales out there, and can pack a socio-political punch as hard as The Sex Pistols or Minor Threat or Bad Brains or Death or Bikini Kill. But their “What if?” question is just a little more specific. They ask: “What if steam technology advanced so much that it shifted power dynamics in unexpected ways?” For example:

In N.K. Jemisin’s story The Effluent Engine, set in the aftermath of the Haitian revolution, a spy seeks the help of an inventor whose plans for an engine that runs off the byproduct of rum distillation might be the key to stopping France from recapturing Haiti.

In Tobias S. Buckell’s story Love Comes to Abyssal City, after humans build underground cities run by analog computers to escape the poison gas aboveground, one woman pushes back against the computer’s design to preserve Victorian morality.

In Caitlin R. Kiernan’s story The Steam Dancer (1896), a girl who was left for dead, her body broken, is found by an inventor who rebuilds her into a steam-powered cyborg, giving her the chance to live a new life as a dancer.

So, just as Catherynne M. Valente—one of the GREAT writers of steampunk—once perfectly explained how a lot of modern steampunk is sorely lacking actual STEAM, I think a lot of it is also lacking actual PUNK. But when these stories have both, they are some of the absolute best. So wipe the steam off your monocle and look out for the good stuff.

I wonder if what really distinguishes the s.p. Is its reckless embrace of gadgetry itself? Perhaps the nostalgia of feeling encouraged by technology’s possibilities, without the reflexive “when it’s NOT evil” we’ve learned to attach?