The Benefits of Single POV Storytelling

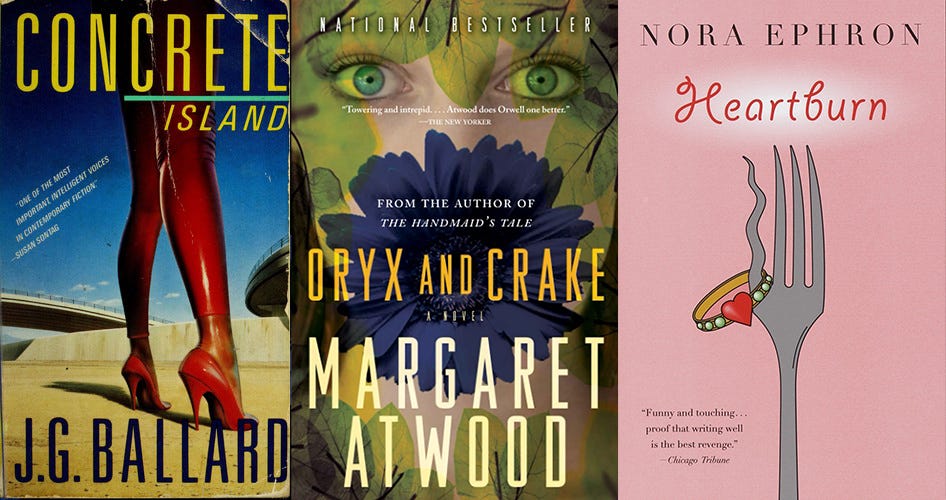

What Oryx & Crake, Heartburn, and Concrete Island all have in common.

The last three books I read—Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood, Heartburn by Nora Ephron, and Concrete Island by J.G. Ballard—are all told through one point of view character, but each use this perspective in very different ways.

On paper, these three stories are very different from one another. Oryx and Crake is about the (apparently) sole human survivor of a post-apocalyptic world populated by primitive and gentle humanoids. Heartburn is an autobiographical novel about a writer who discovers that her husband is having an affair. And Concrete Island is about a man who crashes his car off the highway into an abandoned stretch of land, from which he cannot (or will not) escape. But all three of these stories have two thing in common: they are all told through the lens of one character, and they all make great use of flashbacks.

Oryx and Crake uses flashbacks and remembered stories to paint a full picture of the characters’ interactions and choices that brought him to his current predicament, and to juxtapose the dystopia of its present with the past that created it—a past not so different from our real present.

Heartburn uses flashbacks too, but Ephron uses first-person narration to great effect (as opposed to third) with how she makes the protagonist’s painful remembrances feel triggered by specific interactions, as they often are in real life. Oryx and Crake does this as well, but Atwood also allows some of these flashbacks to take place as whole chapters, which the third person POV allows naturally, as does the nature of our protagonist Jimmy’s circumstances, in which he has nothing but time in his lonely dystopia to dwell on his thoughts.

Concrete Island, like Oryx and Crake, is third person, but, like Heartburn, stays away from lengthy flashbacks. There are remembrances, but they are more like glimpses. We never stay in them long, perhaps because our protagonist Maitland doesn’t want to. Instead, we are dropped into a strange world, and watch Maitland deal with his predicament from close by. We always feel like we are in the room with him, almost as if Ballard is following him around with a notepad. In this way, we can imagine ourselves in his shoes, but never really get a good sense of what’s going on inside, which, in a way, actually gives us a better sense of what’s going on with Maitland, because he doesn’t really know how he feels. But we don’t get a bird’s eye view of the island either. We are as stuck on “the island” as Maitland is.

The shared strength in these three stories:

Their narrative points of view are perfectly suited to tell each story.

Oryx & Crake is, among other things, a book about memory, past vs. future, hope vs. regret. At least half of the story takes place in the past, in part because our protagonist Jimmy doesn’t have much to do in his post-apocalyptic present except take care of the Crakers, those docile creatures not unlike the Eloi in H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine. And the Crakers aren’t great conversationalists, so Jimmy lives in his memories—painful memories, as we learn. He has a very personal relationship with the architects of earth’s destruction, and so it makes sense that he would focus on them.

Painful memories are a big part of all three of these stories.

When Heartburn’s protagonist Rachel discovers that her husband was having an affair, she goes along trying to figure what to do, reflecting on her relationship(s), trying to make sense of what happened. Prior to his crash onto “the island,” Concrete Island’s Maitland was having an affair himself. We learn that he has a wife and child. But his memories crop up whenever he’s wondering whether or not he actually feels attached to them—or the world outside “the island”—at all. And the slow disappearance of these flashbacks over the course of the book makes us—consciously or subconsciously—feel Maitland’s slow alienation from the world outside, from society, as he moves towards an affinity for “the island.”

Basically, the point of view makes the flashbacks feel necessary.

These memories aren’t there to simply convey information. We are in them because of the characters’ pain; they took themselves into these memories for emotional, in-the-moment reasons, and so we are traveling with the characters on a personal journey through the past.

There are points in Oryx & Crake that feel like they are being told from other characters’ points of view, specifically Oryx’s, but these are actually recreations of stories told by Oryx to Jimmy. They are essentially stories that Jimmy is telling himself (and the reader) based on memories of stories that Oryx told him. With these sections, Atwood shows us just how skilled a writer she is. She can use fancy footwork to bring us deeper into the story without sacrificing the characters.

In Concrete Island, Maitland seems either unable or unwilling to escape “the island,” despite there being few physical obstacles in his way. Had this story been told in first person, it would have been too close. We would have called into question his motives early on, and either dismissed them, or accepted them and gotten bored. So much of Concrete Island is about a man who, once he has fallen off the map of modern society, doesn’t really want to go back. But he can’t admit it to himself; he isn’t even capable of fully wrapping his mind around the idea. And he is constantly tricking himself into staying on “the island.” So we need that little bit of distance between us and Maitland because it allows us to call so many things about his state of mind into question, while occasionally tricking us into taking his newfound reality for granted. Is he really going to stay? Does he even want to leave? Is this place even real? We’re not sure. And so we follow him to find out.

It’s also key that we never know what the other two people we meet on “the island” are thinking. It calls their motives, or even their objective existence, into question. There are moments in the story where you wonder if Maitland is delusional. If he can imagine that it’s impossible to escape this clearly escapable place, then is it so far-fetched to think that he might invent other residents of the island to be his foils? We stick to Maitland, which keeps the island a subjective experience, but the third person narration gives us the space we need from Maitland’s inner workings.

Sticking to one main character was what all three of these stories needed. And while writing my current novel, it has taken me several drafts to come to this same conclusion. For me, re-drafting has predominantly been a process of discovering the best way in, the necessary point(s) of view.

What are your favorite single POV stories?

What I’m Reading Now:

Cairo by G. Willow Wilson

The Gift by Lewis Hyde

Winter Counts by David Heska Wanbli Weiden

The Unquiet Dead by Ausma Zehanat Khan

I love this unlikely trio ~ haven't read the Ballard, but look forward to it. The management of POV is such a fascinating thing, too. I've been reading Circe, Madeline Miller's book, which features the cool, measured, bitter tones of Circe's storytelling voice to such good effect, and bumps into Homer's Odysseus in a fascinating way. A critical interest of mine has always been the rise of the unreliable narrator, which sets you at odds with your locutor, to uneasy effect.